Yield reductions with corn after corn

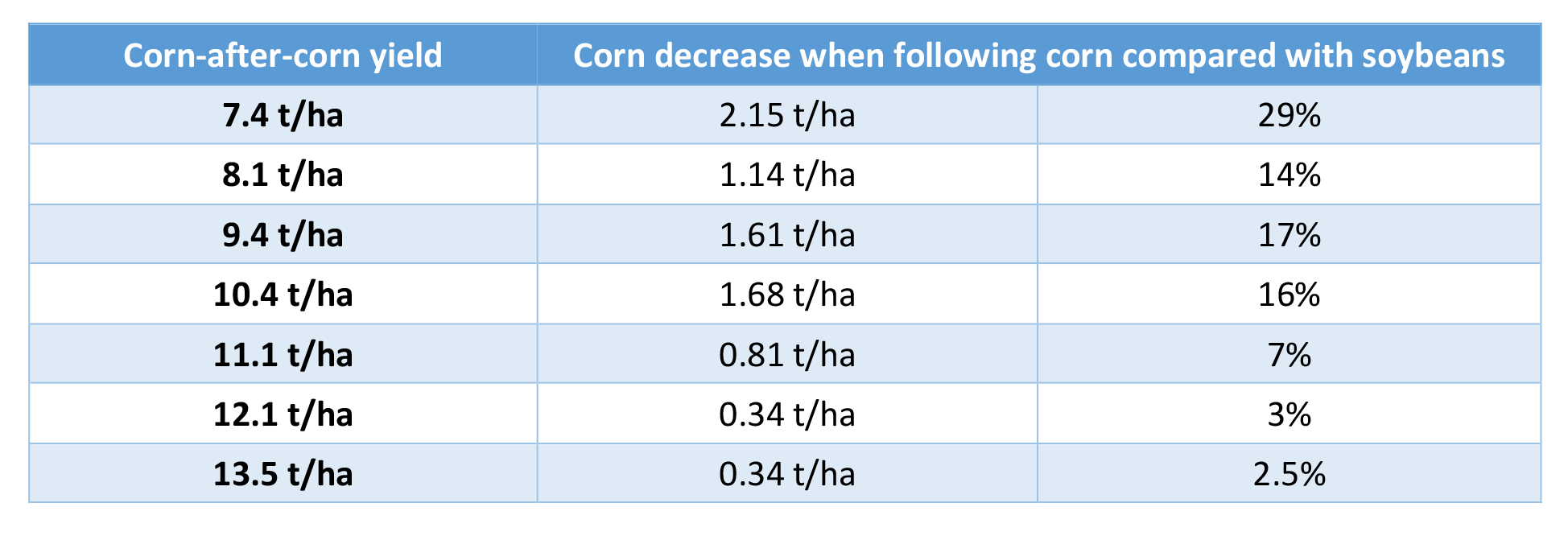

Numerous studies have documented corn yield reductions when corn follows corn rather than other crops, even when all limiting factors appear to have been adequately supplied in the continuous corn system. Yield losses average about 5 -15 per cent, but are much greater some years. Yield reductions are usually greatest when yield potential is low (Table 1).

Table 1. Yield decrease in corn following corn vs. corn following soybeans at different yield levels*.

*Nitrogen was supplied at 225kg/ha. Source: Four-year study at the University of Minnesota Southern Research and Outreach Center at Waseca.

These results indicate that rotated corn is generally better able to tolerate yield-limiting stresses than continuous corn. Other studies as well as grower experience also confirm that major yield losses for corn following corn are often associated with stresses from moisture extremes. This implicates the root system as the most likely source of the problem. In corn-after-corn production, the plant's root system may be limited due to increased populations of soil insect pathogens or in some cases, compaction. Less extensive root systems under continuous corn may cause increased plant stress and yield losses in years when demand for soil moisture is high. Lack of soil moisture during the pollination and early grain-fill stages of corn development, may be most detrimental to continuous corn yields.

To minimise losses in corn-after-corn production systems, growers should select appropriate hybrids, manage corn residue, and adjust soil fertility, weed management and tillage practices to accommodate the change in cropping patterns.

Hybrid selection

Hybrid selection is an important component of successful corn-on-corn production. Growers should always be sure to:

- Select hybrids with proven performance under the diverse environments and stresses their field may encounter.

- Select hybrids with above average drought tolerance. Root mass may be reduced in this production system, hence limiting water uptake the same as during drought conditions.

- Select appropriate hybrid maturities that match corn planting date and seasonal growing degree units, accounting for cooler soils and slower emergence under high-residue conditions associated with corn following corn.

- Choose the highest-performing genetics with defensive traits such as standability and disease and insect resistance required for this production system.

- To assist in selecting hybrids for corn-on-corn fields, Pioneer Seeds provides hybrid ratings for a number of the most desirable hybrid traits for con on corn rotations:

- Leaf, Ear and Stalk Disease Ratings: The incidence and severity of corn diseases can build-up in corn residue. In paddocks with a history of leaf or stalk diseases, growers should choose hybrids with adequate resistance to those specific diseases. Pioneer selects hybrids for resistance to common corn leaf diseases, including northern leaf blight. Ear disease scores include Fusarium, Gibberella and Diplodia. Other disease ratings include anthracnose stalk rot, head smut, Stewart's and Goss's wilt, corn lethal necrosis and maize dwarf mosaic virus complex. Stalk and root strength ratings are also available for all hybrids.

- Insect Traits: Insects are harboured in corn residue and previous corn ground. Growers should choose technologies that defend against these yield-robbing pests. Effective control measures are critical for insect pests, as pressure tends to be highest in the second and third years of continuous corn.

Managing corn residue

A corn crop produces more than twice the residue of a soybean crop, for example. This has advantages in reducing soil erosion, but also presents some challenges. Growers should be prepared to manage corn residue to reduce its negative impact on their corn-on-corn crop.

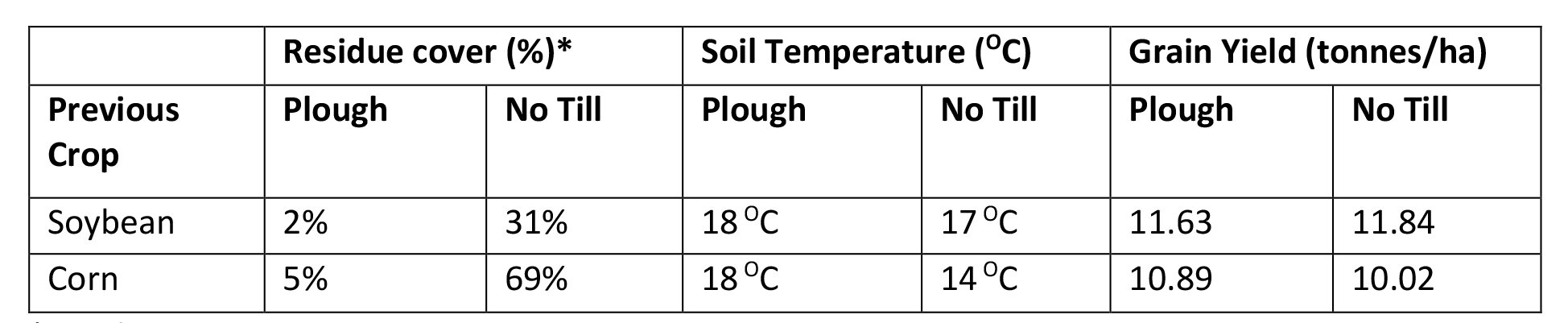

Effects of Corn Residue on Stand Establishment: Excessive corn residue can result in cooler soil temperatures and higher soil moistures at planting time. Residue positioned directly over the row can lower temperatures in the seed zone, delay germination and early growth, and reduce stands and yields (Table 2).

Table 2. Influence of previous crop and tillage on residue cover, soil temperature, and corn grain yield (Lund, et al. 1993).

* At planting.

** Mid-day, in-row temperature at seed depth, averaged for 7 days after planting.

Effects of Corn Residue on Corn Diseases: Corn disease issues generally increase in corn-after-corn production systems, as pathogens survive in corn residue and disease inoculum builds up over time. Leaf diseases such as northern leaf blight, anthracnose, and eyespot are all known to increase in long-term, high-residue crop production systems. Stalk rot and ear rot fungi such as Fusarium, Gibberella, Diplodia and Aspergillus also survive in crop residue and increase in high-residue systems. Seedling disease pathogens also survive in corn residue as well as in the soil, and may increase in corn-after-corn production.

Tips for managing corn residue

Managing corn residue effectively at harvest, with tillage implements and at planting can contribute to successful corn-after-corn production.

- At harvest, knife rolls can replace normal stalk rolls to more aggressively shred stalks at the corn head. Even distribution of residue behind the combine is equally important.

- In areas with cellulosic ethanol plants or feedlots, stover harvest is another option to reduce excess residue, often improving stand establishment and yield (Heggenstaller, 2012).

- Burying corn residue using various tillage operations is another way to manage the additional residue in corn-following-corn production.

- Strip or "zone" tillage is a residue management option that allows growers to retain the benefits of no-till between the rows while gaining the advantages of clean till over the rows.

- Row cleaners, coulters or other residue-management devices on the planter can move residue off the row area to create a suitable environment in the seed zone for more rapid germination and emergence of corn.

Foliar fungicide application

Foliar fungicides can effectively reduce leaf diseases and their detrimental effects on corn yields under intense disease pressure, and when permitted.

Soil fertility

Soil fertility in corn-after-corn production should be based on thorough soil testing and local extension recommendations. Soil tests are needed to determine soil pH and existing levels of phosphorous (P) and potassium (K). The soil pH should be at 6.2 or above for growing corn. A 13.5t/ha corn crop removes about 34 kg of P2O5 and 24 kg of K2O from the soil in the grain; a 4t/ha soybean crop removes about 22 kg of P2O5 and 38 kg of K2O. Growing more corn crops relative to soybeans in the rotation will deplete P more quickly and K more slowly. This would have a negligible short-term effect, but should be watched over time. Banding P and K can improve nutrient uptake efficiencies particularly on soils with pH above 7.2. The N and P components of starter provide the early growth enhancement.

Determining nitrogen (N) rates for corn after corn involves compensating factors - yields are likely to be lower, so overall N use by the crop will be reduced; but because N is immobilised by corn residue, additional N must be added. For example, if using yield-based calculations of N requirements, scientists recommend that growers adjust their yield goals to about 10% less (5 to 15% less) for corn following corn vs. soybeans. Once N needs are determined by this or other methods, producers should increase their N fertiliser by 13 to 23 kg/ha to compensate for N immobilised by the decomposition of corn residue in the soil. Nitrogen rate recommendations vary and growers are encouraged to follow their local extension recommendations regarding N fertilisation.

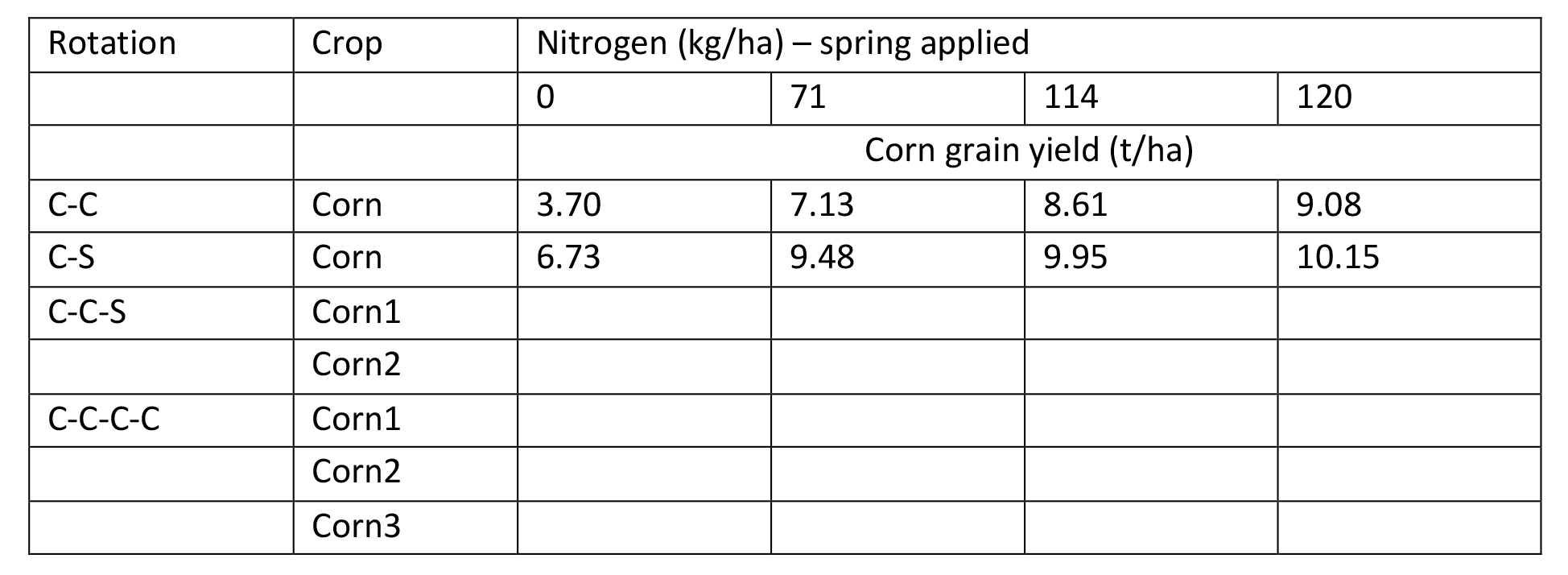

Nitrogen rate has bee n a component of numerous rotation studies over many years. These studies generally show that increased N alone does not compensate for the reduction in corn yield when following corn vs. soybeans (Table 3).

Table 3. Effect of crop rotation and nitrogen rate on average corn yields. Mallarino and Pecinovsky. 1999*.

Corn1, Corn2 and Corn3 = 1st, 2nd and 3rd year of corn after soybeans, respectively. *20-year study - Iowa State University.

In this study, corn following corn yields never equaled those of corn following soybeans, regardless of the nitrogen rate applied. At 160 lbs N/acre, this difference averaged 19 bu/acre, or 13% lower yields following corn. At 240 lbs/acre of N, the difference was 14 bu/acre, or 10% less yield following corn vs. soybeans. However, a recent study showed that additional N may, in some cases, overcome much of the yield reduction associated with corn after corn (Mallarino and Rueber, 2011).

Weed management

Weed management is an important issue when changing from corn following soybeans to corn on corn, as certain weeds may be more problematic. Growers should monitor fields for any increase in specific weed pressure and employ appropriate management solutions.

Volunteer corn is much harder to manage in a corn crop than in a soybean crop. Therefore, growers should strive to prevent volunteer corn by minimising stalk breakage, ear droppage and harvest losses. This begins with regular scouting of fields in the fall and harvesting fields early if they are at risk of lodging or dropping ears. Adjusting and maintaining the combine helps to minimise kernel loss during harvesting.

When rotating corn with soybeans, an obvious opportunity exists to rotate herbicides as well. Rotating herbicide modes of action helps ensure long-term weed management success by preventing weed shifts and/or weed resistance. When switching to corn-after-corn production, growers should continue alternating herbicide modes of action and using mixtures or sequential applications of herbicides with different modes of action.

Tillage systems

In studies conducted at Purdue University, tillage system affected the penalty for growing corn after corn rather than in rotation with soybean. No-till systems suffered the greatest penalty followed by conservation till and then moldboard plowing. However, in some high-yield environments, the penalty under no-till systems was no different than that of the other tillage systems.

Effective residue management under no-till systems may help to minimise the yield losses associated with switching from corn after soybean to corn after corn. Strip or "zone" tillage or row cleaners can be used to remove crop residue from over the row while retaining residue between the rows. Some tillage and seedbed tips are listed below:

Tillage and seedbed tips

Plan for tillage that builds a good seedbed for next year, including adequate labor and equipment to complete tillage in the fall. Spring tillage operations are often delayed due to cooler and wetter conditions in continuous corn.

Check for soil hard pans and use appropriate tillage to break up compacted soil layers.

Full-width tillage systems should focus on sizing and incorporating residue to speed decomposition.

In northern areas and on poorly drained soils, strip or zone tillage systems can create a warmer seedbed versus no-till while requiring less fuel than full tillage systems.

Equip planters with row cleaners to move residue off the row and achieve more consistent soil warm up and seedling emergence in the spring.

Closely monitor the wear on planter double disc openers to ensure they cut clean and form a good seed furrow.

Conclusions

Though some yield decrease is expected when switching from rotation to corn after corn, yield reductions can be minimised by selecting appropriate hybrids, dealing effectively with corn residue, and adjusting key production practices. In addition to the management considerations described above, the following list can help mitigate yield-reducing issues in corn-after-corn production systems.

Choose fields with good drainage, medium-textured soils with ample water-holding capacity, and adequate P and K levels.

Consider planting corn-after-soybean fields first, to allow wetter corn ground the opportunity to dry. Delaying planting until soils are above 50 F (and likely to remain there) can help reduce seedling diseases and improve stands.

When planting, ensure that soil conditions are dry enough to prevent sidewall compaction of the seed furrow, which limits early root growth and may cause uneven stand establishment.

Routinely scout and monitor fields to identify any problems early. Look for stand establishment issues, nitrogen shortages, insect buildups, disease outbreaks, weed problems and moisture stress effects.

Be diligent to prevent soil compaction on corn-after-corn fields. Avoid excess traffic with combines, grain wagons and trucks in the fall and fertilizer and manure applicators in the fall or spring, especially if fields are wet.

Crop Insights by Steve Butzen, Agronomy Information Manager